“Wow,” the preteen customer says, “it’s like you’ve read every book in here.”

I look around the room. Vibrant bookshelves are stuffed with children’s graphic novels, and eclectic comic ephemera hangs from the ceiling and the walls.

“Sometimes it feels that way,” I say. “I get to read a lot of the books because it’s my job to tell you about them.”

The kid’s eyes get big. “That’s so cool.”

It is pretty cool. Sometimes I forget.

♠

I’ve been working at a bookstore for over 2 years now, about as long as I’ve lived in Toronto. The bookstore is funky and dysfunctional. The bookstore is its own animal, its own body, and all of us are just cells traveling through its twisting channels. The bookstore has mercurial moods that can shift at the drop of a hat, but you learn to predict them by minute signs. The bookstore started as a summer job, but has since shapeshifted into something I can name, shakily, as a career, if people ask me—doesn’t something become a career once your apartment has started to overflow with it; once you begin to find little bits of it on you, in your pockets, at the bottom of your shoe? Every morning when I let myself in I take a big whiff into my lungs of vital ink-and-paper air. Every evening when I leave I’ve had more than my fill.

♠

My favourite child-customer comes in with his parents one afternoon. He’s critical of my graphic novel suggestions but has, over time, come to cautiously trust me. After grilling me on my comics know-how, he tells me his birthday is coming up.

“You’re turning seven?” I say.

His eyes go wide. “How did you know?”

“A few months ago you told me you were six and a half.” (When greeting him that day I asked, What’s new? and he replied, I’m six and a half. He’s a quipper.)

He also tells me that, ahead of turning seven, he can cartwheel, dive, and whistle. “That’s pretty impressive,” I say.

♠

When I interviewed for the bookstore, I was asked if I knew anything about comics. My reply was something like not much, but what a lie that turned out to be. This job has unearthed so much knowledge from the back-dusty-corners of my hippocampus that it sometimes feels like I was storing it away for this specific purpose. I’ve been intimately familiar with comics for most of my life; it’s just that I grew up and forgot it all.

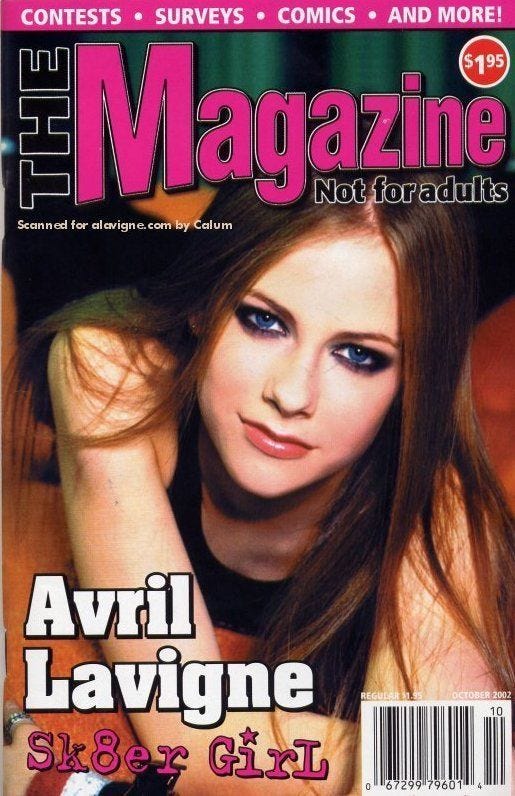

My parents met while working at a children’s animation studio, so I grew up drawing on stacks and stacks of recycled storyboards. Maybe that’s why some of the first art I made, assisted by grown-up hands, was comics-adjacent. Even before I could write, speech bubbles curled up out of people’s mouths like serpents’ tongues, like smoke. Once I could read, I devoured comics; Archie digests—mostly Betty & Veronica, for the fashion, and Jughead, for the food; the serialized stories in the iconic Canadian Magazine Not For Adults; the Sunday paper strips, and whatever else was eye level at the grocery store checkout line.

And then there was manga: in grade two, courtesy of the school book fair, I fell in passionate love with Katy Coope’s How to Draw Manga—in hindsight, maybe not the best way to learn the craft, but nevertheless an essential skill to have in 2002, when every kid was watching Pokemon, Sailor Moon, and Dragon Ball Z. I had never seen any of those shows, but my dad had brought home Cardcaptors (The North-Americanized dub of Cardcaptor Sakura) from work the year prior, and I was hooked. No matter which Japanese import you were watching, it was extremely valuable cultural currency to be able to draw chibi characters for your classmates.

Comics felt scarce to a kid growing up in the small-town-Ontario 2000s, and manga even more so. My friends and I passed around pilfered volumes like holy texts. My family would make semi-annual pilgrimages to a wholesale bookstore where they sold remaindered manga at $1/piece—I’d always leave with a stack, even if they were nonconsecutive volumes of series I’d never heard of before. I took what I could get; our small-town library branch carried hardly any manga (except for single issues of Tania Del Rio’s manga-inspired reboot of Sabrina the Teenage Witch, which I worshipped), and my school’s library only briefly shelved Shojo Beat magazine until someone got scandalized by Ai Yazawa’s Nana.

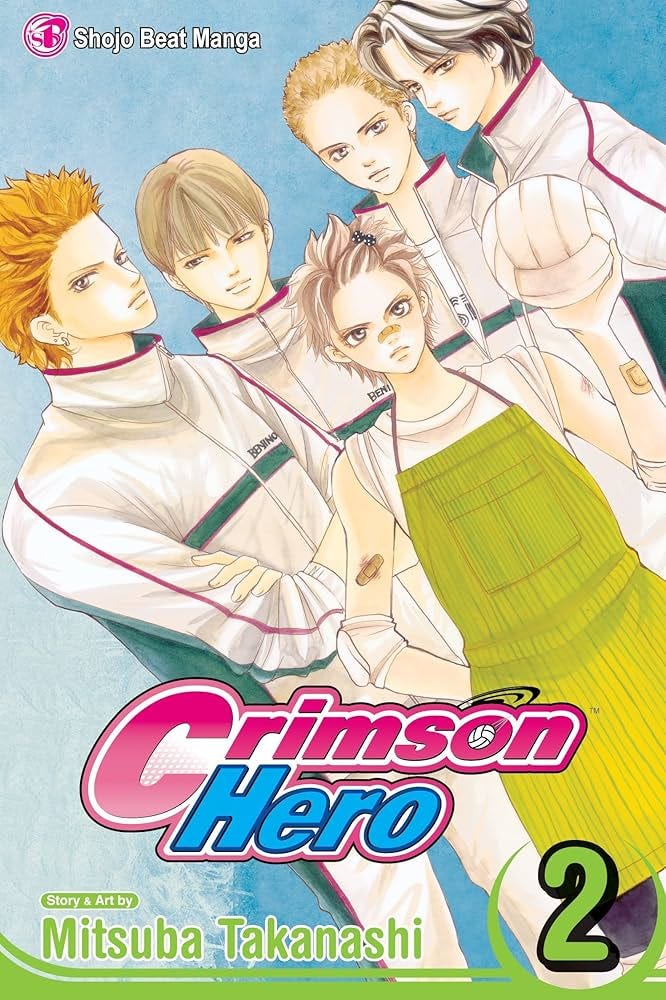

Despite manga’s relative scarcity during that time, I managed to become voraciously acquainted with pretty much the entire 2000s catalogues of both Shojo Beat and Tokyopop. Many of my most influential reads like Crimson Hero, Lovely Complex, Full Moon, and various CLAMP titles are out of print now, but occasionally I’ll find a stray volume in the bookstore’s inventory and get lost in the stories all over again. I’d need a whole other essay’s worth of words to describe my adolescent love of shojo manga, and all its North American offshoots (e.g.: Dramacon; W.I.T.C.H.), but suffice to say these had a huge effect on the development of my brain/style/personality, not to mention my own young writing.

Sometimes, I would write stories about people working in bookstores—I used to write a lot of things I hadn’t yet experienced, many of which have since come to pass in my own life (Once, trying to characterize a charming romantic lead, I described a tall, shy, curly-haired man who treasured a collection of Winnie-the-Pooh books. He manifested a few years later, and took me on a handful of very nice dates). If you carry a story with you long enough, I think, it will eventually work its way into your own story. This is how the bookstore feels sometimes: like an eerily familiar stack of wishes I’ve written down throughout my life. On the days it’s going well, I remember what a wish it once was to scrape by in a big city, living alone and peddling books.

Of course, on the days it’s going poorly, it feels like a bad story—like one of those anxious dreams in a shoddily-constructed remembering of a place (there are only three walls, and the fourth wall is impenetrable forest; sometimes it rains from the ceiling and all the paper gets soggy; at closing time, we must all do an elaborate line dance; the books are organized alphabetically by the first letter of their last sentence). In the dream, you’re always trying to get somewhere and a thousand things get in your way. This, too—the exhaustively creative chaos-source—I imagined when I wrote my dreamy bookstores, like I knew even then that you couldn’t have one without the other.

In high school, via DeviantArt (this website was once a haven for finding cool, off-beat artists; now it’s mostly an AI repository) and Tumblr, I stumbled headfirst into the world of independent webcomics—this was very pre-Webtoon, when you had to really forage for good comics online, hunter-gatherer style. One of my favourite activities on the 2010s Internet was to get deeply wrapped up in artists’ comic development process, watching as they slowly shared concepts and character designs. I spent hours poring over the pages of Plume, Always Raining Here, Dream*Scar, and Lackadaisy; the work of artists like Kate Beaton and Phobs; and about 5000 other virtual people and places I’m still in the process of dredging up from my brain. Some of the comics whose progress I followed religiously (like Mias and Elle) are still being updated today. Hundreds of others, like Petra Erika Nordlund’s Prague Race, are long gone—deleted or lost to digital decay.

As so many series quietly went out of print, and unfinished comics disappeared from the web, I had started my own long process of forgetting. At some fated point on the cusp of adulthood, I set aside all those works I so greatly loved, that had such a hand in shaping my tastes as an artist, writer, and reader—because it wasn’t very ‘cool’ to care about comics, and they weren’t ‘serious’ art anyway.

♠

A different kind of growing-up happens at the bookstore. Since starting there, I’ve been cured of my internalized nerdphobia and relearned to embrace the things that make me geek out hard—and, as a result, I am the coolest I’ve ever been, because I’ve never cared less about whether I’m doing culture consumption right. Working in a place where you can shamelessly gush about the fanfiction you read as a teen (or are reading right now) and have the people around you react with wholehearted interest will do that for you. I’ve realized, in ways that had never occurred to me before, how so many of my so-called nerdy interests can converge to make sense in one place. I hope this is the way people—kids especially—can feel when they step into a shop like this.

In a time of renewed puritanical book-banning fervour, working in a place that upholds readers’ rights to access diverse stories has felt like a tenuous lifeline. People are afraid of what kids might read, and what they might thus learn about the world. But all that fear is wasted—the stories are already written; the kids already know they’re out there; and they’re already in the process of building their own truths. The bookstore is a place where one can practice the art of listening to kids, who have a much better understanding of what stories they’re ready for than any adults ever have. Ask an adult what the child they’re shopping for likes to read about, and you’ll often get an answer like, uh, I don’t know, dragons? Ask a librarian, and you might hear that they won’t stop asking me for that manga stuff, but I really don’t get the appeal. Ask a kid, and they’ll tell you I’ve already read all those series—do you have anything scarier? Helping young people have a say in their own reading choices is a magic-making thing to be a part of. It’s so easy to forget how it felt to be a kid fighting for a good read.

In the bookstore, the divide between Books and Children’s Books is delineated by an open doorway. These days, there’s no shortage of kids’ comics—the shelves are packed. From my desk, I watch patrons hesitate at the threshold as if waiting to be invited in. Is this part of the bookstore? They’ll ask, peering in cautiously. Yes, I’ll say, it’s the kids’ and teens’ section, and then they duck back out like they’ve been singed, retreating, still-smoking, to the more artistically-esteemed world of comics made for adults. And yet, contained in this room are some of the most poignant and beautiful pieces of art I’ve ever read. And some of the most fun and stupid. It’s so interesting being a grown-up sentry for kids’ comics, and watching other grown-ups dismiss them as I would’ve done too, just a few years ago. How I’ve grown since then; how much of myself I’ve remembered.

Am I a grown-up now? Does growing up make you a grown-up? I’m almost thirty, and I still fumble words when leaving a voicemail. I do know how to send an invoice and how to slice a bagel cleanly, but I do not know how to do a cartwheel. I haven’t dived in years. And every day, I read comics made for kids.

♠

My favourite customer returns post-birthday. He’s come in for the latest volume of a series I recommended (he initially snubbed it, but has, at some point since, changed his mind. He does this often, exercising his young autonomy).

“I’m finally seven,” he reports, once we’ve gotten business out of the way.

“And how does it feel to be seven?” I ask. “Do you feel any older?”

He thinks about it for a minute, before producing another one of his all-time quips.

“Well,” he says, “I don’t feel any taller.”

P.S. It’s the ShortBox Comics Fair this month, so if any of this has inspired you to go love on some comics, you can spend a few dollars right now on a great new read.

Thanks as always for reading. It’s been quite a while since I’ve shared any writing here, so it felt right for it to be about the place my brain (and the rest of me) has been spending most of that time.

♥happy reading,

Emmali